Recovering from lung or chest surgery can make your own breathing feel unfamiliar. Sticky phlegm that will not move, a heavy chest, and fear of taking a deep breath because it might hurt or “pull” on the scar are all common experiences.

The good news: simple, evidence-based breathing techniques can help you clear mucus more gently, improve lung expansion, and reduce the risk of complications. One of the most powerful tools is the Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT) – and, later in recovery, selected breathing trainers can support your respiratory muscles.

Quick answer – how to clear phlegm from your lungs after surgery

After surgery, one of the safest ways to clear phlegm is to combine gentle deep breathing, chest-expansion breaths, and a controlled “huff cough” in a structured sequence called the Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT). ACBT helps air get behind mucus, move it from smaller airways to larger ones, and clear it with fewer, more effective coughs. In many hospitals across Europe, the UK, North America and Australia, ACBT is part of standard physiotherapy. Later in recovery, your team may also recommend respiratory muscle training (RMT) with a device to strengthen breathing muscles and lower the risk of future complications. Always follow the plan agreed with your doctor or physiotherapist.

My lung surgery story: why breathing training mattered

I am not writing this as a distant observer. I am a lung surgery patient myself.

After having part of my right lung removed for early-stage cancer, I walked into recovery with two big questions:

- “Is the tumor really gone?”

- “Will I ever feel safe in my own breath again?”

In the first weeks after surgery, every deep breath felt huge. I was afraid of pulling on the scar. I coughed carefully because I did not want to feel pain. Lying in bed, I could sense the heaviness in my chest and the sticky phlegm that did not want to move.

A few things changed the trajectory for me:

- A kind physiotherapist who sat by my bed and taught me breathing control, deep chest expansion and huffing so I could clear mucus without brutal coughing.

- Nurses who gently insisted that I sit up, stand and walk even when I was tired – because movement is medicine for lungs.

- Later in my recovery, when I was back home and past the acute phase, I added a breathing trainer (Airofit) on and off. On days when my chest felt “lazy” or my breathing felt shallow, those short sessions reminded my lungs how to work — and reminded me that I was not powerless.

Airofit did not replace surgery, scans, or medical care. But it gave me:

- A structured way to strengthen my breathing muscles

- A feeling of agency and progress in a long recovery

- A way to reconnect with my breath instead of fearing it

If you’ve undergone surgery or suffer from lung disease, it’s crucial to discuss any device or training plan with your team. I share my story because I know how powerful it can feel to have a simple, daily breathing practice that supports both your lungs and your courage.

Why phlegm builds up after surgery – and why it matters

Under normal circumstances, your lungs have a smart self-cleaning system:

- Tiny hairs (cilia) constantly move mucus upwards

- You take regular deep breaths without thinking

- You move, stretch, and naturally clear small amounts of secretions when you cough or clear your throat

After surgery, that system is disrupted:

- Anaesthesia slows the breathing drive and cough reflex

- Pain encourages shallow, protective breaths

- Fear of hurting the incision makes you avoid deep breathing and coughing

- Bed rest reduces lung expansion and circulation, especially in the lower lung zones

When you breathe too shallowly for too long, mucus can settle in the airways. This raises the risk of:

- Atelectasis – small areas of lung collapse

- Infections and pneumonia

- Longer hospital stays and slower recovery

In major chest surgeries, postoperative pulmonary complications (PPCs) are unfortunately common. Studies of complex procedures such as cardiac and major abdominal surgery show that, without targeted breathing training, a significant percentage of patients develop PPCs like pneumonia and atelectasis. When structured inspiratory muscle training is added before surgery, these complications and the length of hospital stay can be reduced in many patients.

The takeaway: mucus and shallow breathing after surgery are not just uncomfortable – they are risk factors. And they are not just “bad luck”: they are modifiable with the right support.

Breathing mechanics 101: understanding your foundation

To make sense of ACBT, it helps to understand what is actually moving when you breathe.

Think of three key players:

1. The diaphragm

Your diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle sitting under your lungs. When it contracts:

- It moves downward

- Your belly softens and rises

- Air is drawn into the lower parts of your lungs

After surgery, pain, fear, and guarding can make the diaphragm move less. You may shift into shallow, upper-chest breathing instead.

2. The ribs and chest wall

Your ribs form a flexible cage. They can expand:

- Forward

- Sideways

- Backwards

In a healthy deep breath, your lower ribs widen in all directions, like an umbrella opening. After surgery, we often see:

- Stiffness around scars

- Protective muscle tension

- A “frozen” feeling on one side of the chest

Gentle chest-expansion breaths help reopen these areas.

3. The airways and mucus

Your lungs branch like a tree:

- Large airways near the top

- Smaller and smaller branches deep inside

To clear phlegm effectively, air needs to:

- Reach behind the mucus

- Push it upwards, step by step

- Bring it into larger airways where a cough can clear it

If you only take tiny breaths, air never reaches the lower branches, and mucus stays trapped.

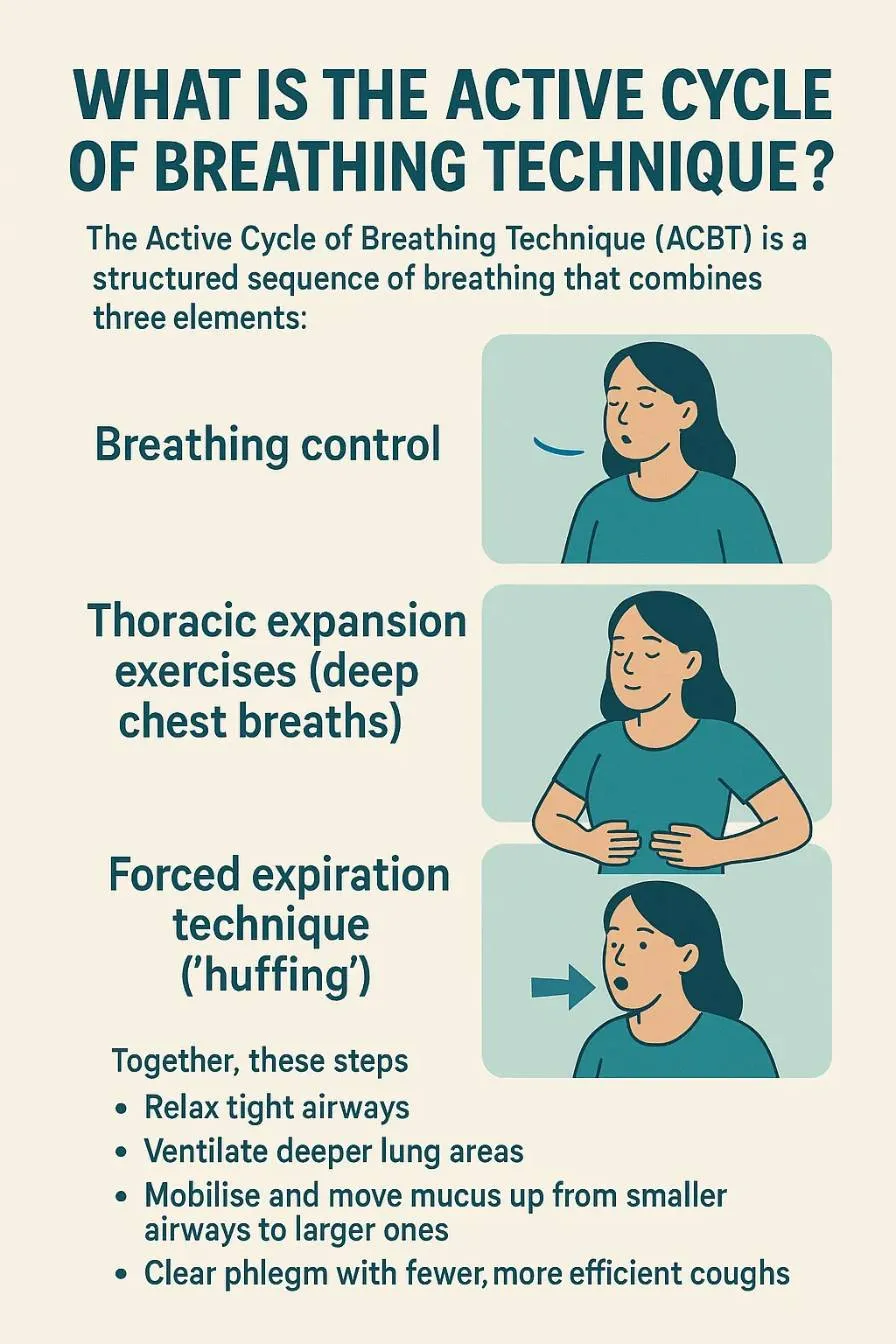

What is the Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT)?

The Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT) is a structured sequence of breathing that combines three elements:

- Breathing control

- Thoracic expansion exercises (deep chest breaths)

- Forced expiration technique (“huffing”)

Together, these steps help you:

- Relax tight airways

- Ventilate deeper lung areas

- Mobilise and move mucus up from smaller airways to larger ones

- Clear phlegm with fewer, more efficient coughs

ACBT is:

- Non-invasive and equipment-free

- Used in hospitals and rehab programs across Europe, the UK, the US and Australia

- Recommended for both chronic lung diseases (like cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis and COPD) and postoperative care

Systematic reviews show that ACBT can:

- Increase the volume of sputum you actually clear

- Improve lung volumes and oxygenation

- Reduce the feeling of breathlessness

- Perform at least as well as other airway-clearance methods, with few or no adverse events when taught correctly

Large health organisations, including national health services and specialist foundations, publish patient-friendly instructions for ACBT because it has such a solid base in physiotherapy practice.

ACBT is simple enough to learn – but powerful enough to be used in major hospitals. The key is good instruction and listening to your own body.

If you’re healing after lung surgery, clean air matters. See the Best Air Purifiers for Post-Lobectomy Recovery (2025)

Step-by-step: how to do the Active Cycle of Breathing Technique

Always follow the exact version your physiotherapist teaches you. The outline below is a general guide.

1. Breathing control – calming your system

Goal: Relax your airways and reduce tension.

- Sit or lie in a comfortable, supported position

- Place one hand over your upper belly or lower ribs

- Breathe gently in through your nose and out through relaxed lips

- Let your belly and lower ribs rise softly as you inhale and fall as you exhale

- Keep your shoulders soft and your upper chest quiet

Continue for 20–30 seconds or about 6 easy breaths. If you feel anxious or tight, stay here a bit longer.

2. Thoracic expansion – deep, targeted breaths

Goal: Ventilate deeper lung areas and loosen secretions.

From breathing control:

- Take a slow, deep breath in through your nose

- Let your lower ribs expand outwards and backwards, as if you are filling the sides and back of your rib cage

- At the top of the inhale, hold your breath for 2–3 seconds to let air travel into smaller lung areas

- Breathe out gently and completely, without forcing

Take 2–3 of these deep breaths, then return to breathing control for a few relaxed breaths. Repeat this pattern as guided by your therapist.

Once you learn ACBT, you may want to try other breathing techniques. Here’s How Breathing Techniques Can Transform Your Respiratory Health

3. Huffing – moving mucus upwards

Goal: Move mucus from smaller airways to larger ones without harsh coughing.

A huff is like trying to fog up a mirror:

- Take a medium or slightly deep breath in

- Open your mouth and throat

- Exhale actively but not violently, making a soft “ha” sound

- Focus on pushing air out from your chest, not squeezing your throat

You might use:

- One or two long, gentle huffs from a mid-size breath to mobilise mucus from deeper airways

- One shorter, slightly stronger huff from a small-to-medium breath to bring mucus higher

When you feel phlegm reach your upper chest or throat, allow yourself one or two controlled coughs to clear it. Then return to breathing control.

Struggling with wheezing, tightness, or shallow breathing? This guide explains Understanding Asthma: How To Improve Lung Function Naturally

A simple example cycle

A typical ACBT cycle might look like this:

- Breathing control – 20–30 seconds

- 3 thoracic expansion breaths with 2–3 second holds

- Breathing control – 20–30 seconds

- 1–2 huffs, then cough if needed

- Rest and breathing control

You can repeat this cycle several times, depending on how you feel and what your physiotherapist recommends.

Limitations and when ACBT is not enough on its own

ACBT is powerful, but not magic. A few important points:

- It requires active participation. You need enough understanding and energy to follow the sequence. Very frail or confused patients may need more hands-on support.

- Instruction quality matters. The technique works best when a physiotherapist adjusts the number of deep breaths, the length of breathing control, and the strength of huffs for your specific condition.

- Effectiveness varies. ACBT has strong evidence in chronic sputum-producing diseases and after certain surgeries. Other conditions may need different or additional techniques.

- It is a complement, not a replacement. ACBT works best alongside early mobilisation, effective pain control, medication, and good overall postoperative care.

If you feel more breathless, dizzy, or uncomfortable at any point, you should pause and talk with your healthcare team.

Mucus-clearing devices and breathing trainers

Breathing techniques like ACBT are often the first line of airway clearance. In some cases, your healthcare team may also recommend devices to help move mucus or to train your breathing muscles. No single device is “the best” for everyone – the ideal choice depends on your lung condition, your flow rates, your coordination and what your physiotherapist feels is safest for you.

Below are the main categories, with examples of well-known, widely used devices.

1. PEP (Positive Expiratory Pressure) devices

- You exhale against gentle resistance through a mask or mouthpiece.

- This back-pressure helps keep airways open longer.

- It allows air to get behind mucus and push it towards larger airways.

PEP systems are common in hospital physiotherapy departments in Europe, the UK, the US and Australia. Your therapist will usually select the resistance level and show you how to clean the device safely.

Better breathing boosts clarity and focus — especially during recovery. Learn The Connection Between Breathing And Concentration

2. Oscillating PEP devices (OPEP)

Oscillating PEP devices combine resistance with small vibrations in the airflow to help loosen sticky phlegm. They are particularly common in chronic mucus conditions such as bronchiectasis and cystic fibrosis, and sometimes used after infections or surgery.

Examples include:

- Aerobika

- A handheld device that provides oscillating PEP when you breathe out through it.

- Many users describe easier mucus clearance and better breathing capacity when used regularly, especially alongside physiotherapy exercises.

- It is often praised for being relatively easy to use and clean, which is important for infection control.

- Acapella (Choice, Green, Blue models)

- Another well-established oscillating PEP device used worldwide.

- Reviews often mention that it “actually works” to loosen and mobilise mucus in conditions like bronchiectasis or after pneumonia.

- Some users find the instructions confusing at first, which is why a clear demonstration from a physiotherapist is so valuable.

- AirPhysio

- A portable, drug-free oscillating PEP device marketed for daily use to mobilise mucus and support lung health.

- Users often highlight that it is quick to use and easy to integrate into morning or evening routines.

All oscillating PEP devices require careful cleaning according to the manufacturer’s instructions to reduce infection risk.

3. Respiratory muscle training (RMT) devices

Respiratory muscle training devices strengthen the muscles you use to breathe in and out by making you work against resistance. They do not directly shake mucus but can indirectly support airway clearance by improving the depth and quality of your breaths.

One of the most established brands in this space is:

- POWERbreathe (Classic and K-Series)

- Mechanical and electronic inspiratory muscle trainers used in both sports and medical rehabilitation.

- Clinical trials show improvements in inspiratory muscle strength, pulmonary function and exercise tolerance when devices are used regularly as part of a structured program.

Devices like Airofit also belong in this RMT category. I personally use my Airofit as part of long-term lung recovery – always within the limits my medical team and energy levels allow. For many readers, RMT will be a “phase two” tool, added after the acute postoperative period when scars have healed and breathing is more stable.

Large systematic reviews and meta-analyses show that structured inspiratory muscle training before major surgery can:

- Reduce postoperative pneumonia and atelectasis

- Reduce overall postoperative pulmonary complications

- Shorten hospital stays in many patient groups

These effects have been demonstrated in adults undergoing cardiac and major abdominal surgery, and more recent data suggest similar benefits in lung cancer surgery and other high-risk procedures.

4. Other options

- High-frequency chest wall oscillation vests – inflatable vests that create rapid compressions on the chest to help loosen mucus, mainly used in complex chronic lung diseases under specialist care.

- Simple helpers – adequate hydration (if allowed by your team), humidified air, prescribed nebulised saline, gentle movement and posture changes, all of which support mucus clearance.

Important caveats when choosing a device

If you are considering any mucus-clearing or breathing trainer device, it is essential to keep these points in mind:

- Always consult your doctor or physiotherapist first. The right device and resistance level depend on your diagnosis, your lung function and your current recovery stage. Some devices are not appropriate for certain heart or lung conditions.

- Hygiene is non-negotiable. All devices that come into contact with your breath must be cleaned exactly as described in the instructions. Poor cleaning can increase the risk of lung infections.

- Individual results vary. One person may respond very well to a particular device, while another finds it uncomfortable or ineffective. There is no single “best” device for everybody. Your preferences, your coordination and how well you can fit the routine into daily life all matter.

- Availability and regulations differ by region. Some models are widely available and certified in the EU, UK, US and Australia, while others are currently sold only in certain markets. Check local availability, certifications (such as CE marking in Europe) and any regional medical device regulations.

In this article and future reviews, I mention these devices as examples of commonly used tools, not as one-size-fits-all prescriptions. Your healthcare team remains your primary guide when it comes to choosing, using and monitoring any device.

Safety: when to pause and when to call your doctor

Stop breathing exercises or device use and rest if you experience:

- Dizziness or feeling faint

- New sharp chest pain

- Sudden, intense breathlessness that feels different from your usual pattern

Contact your doctor, emergency service, or surgical team promptly if you notice:

- Blood in your phlegm (more than a few streaks)

- High fever, chills or feeling acutely unwell

- New or rapidly worsening shortness of breath

- New chest pain, especially if it is heavy, squeezing or radiating

- New weakness, confusion, or trouble staying awake

If you are unsure, it is always safer to call and ask. This article is for general information only and does not replace personal medical advice or diagnosis.

Bringing it together: an example day in recovery

Every person and every surgery is different. But a gentle, evidence-informed day might look like this after your team has cleared you for breathing exercises:

- Morning

- Pain medication as prescribed

- Short walk in the corridor or around your home

- One or two ACBT cycles: breathing control, chest-expansion breaths, huff, rest

- Midday

- Sit in a chair instead of lying in bed

- Gentle stretches for shoulders and upper back

- Another ACBT session if you feel congested

- Afternoon / Evening

- Short, comfortable walk

- If your team has recommended it: one short session of respiratory muscle training with your device at very low resistance

- A calming breathing control practice before sleep to reduce anxiety

The goal is not perfection. The goal is a pattern of regular movement, deepening breaths and gentle clearance, layered on top of good medical care.

Key takeaways

- After surgery, phlegm build-up and shallow breathing are common but important to address because they increase the risk of pneumonia and lung collapse.

- The Active Cycle of Breathing Technique (ACBT) is a simple, equipment-free sequence that can help relax airways, reach deeper lung areas, and move mucus upwards so you can clear it more effectively.

- ACBT is supported by clinical studies and systematic reviews, and is used in hospitals across Europe, the UK, the US and Australia for both chronic lung diseases and postoperative care.

- Respiratory muscle training (RMT) with devices – including trainers like Airofit and POWERbreathe – has strong evidence in high-risk surgical patients and chronic lung conditions for reducing complications and improving breathing muscle strength when used correctly.

- Your safest path forward is a combination of professional guidance, early mobilisation, tailored breathing techniques, and (if appropriate) structured device-based training, always adapted to your energy, pain level and overall health.

You are not expected to navigate this alone. Ask your team to teach you ACBT, review your technique, and help you decide if and when a breathing trainer fits into your story.

About The Author

Anita Lauritsen

Anita Lauritsen is the founder of BreathFullLiving.com, a space devoted to exploring the connection between air, breath, and well-being. After surviving early-stage lung cancer and undergoing a lobectomy, Anita was inspired to share her journey and advocate for greater awareness of lung health. Through her writing, she offers compassion, insight, and practical guidance for anyone seeking to breathe more fully—both in body and in life.